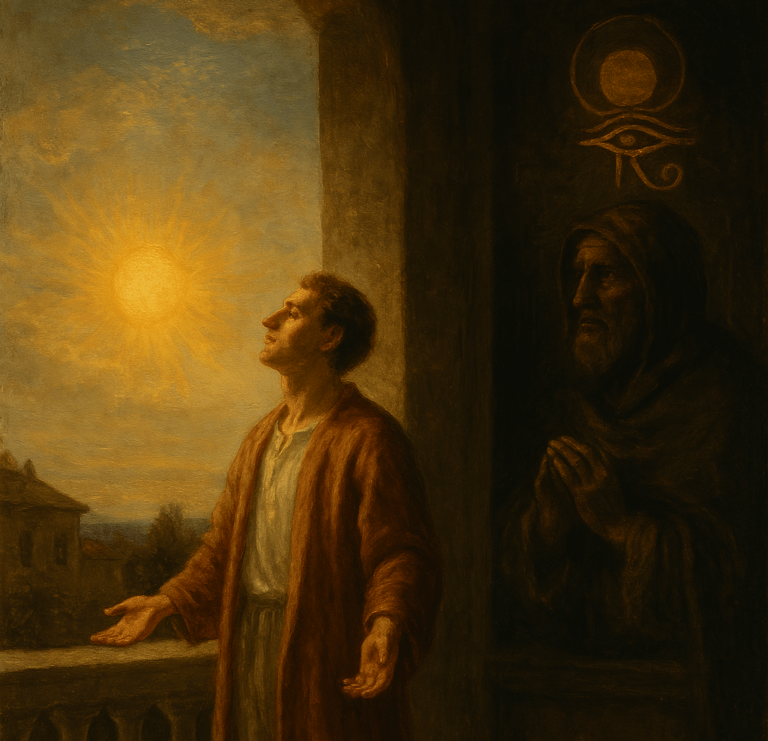

Facing the World Without a Story is Hard

There are moments when you encounter a text, where it feels less like reading and more like being recognized. Recently, I have been reading The Crisis of Narration by Byung-Chul Han. And there has been one particular chapter which I seem to return to again and again. It is called “Bare Life.” In it, Han … Read more