David Hume’s inquiry into the origin of ideas is a foundational aspect of his philosophical work, aiming to clarify the nature of human perception and understanding. In section II of An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding this exploration begins with a crucial distinction between two modes of the mind: impressions and ideas.

After this distinction is made, Hume’s analysis delves into the faculty of imagination, highlighting its limitations despite its apparent boundlessness. He argues that imagination is confined to manipulating the materials provided by the senses and experience. This leads to the formulation of Hume’s Copy Principle, which posits that all ideas are copies of impressions. Finally, through a series of arguments and examples, he demonstrates how complex ideas can be traced back to simple impressions and how the absence of certain sensory experiences limits the formation of corresponding ideas.

Impressions and ideas

The first thing Hume does is to notice the difference between what is being perceived by the mind and what is being thought by the mind. These, he posits, are two different modes of the mind. It is indeed clear to most that when someone is angry, it is a very different sensation from the one present when merely reflecting on the idea of anger. The former state is more vivacious, has more force. The same goes for being in love compared to understanding that a friend is in love with someone.

Hume does mention that there few cases where the contrary is true, when the idea of something might outshine the actual state. But the people experiencing such scenarios are always suffering from mental disorders or madness in some capacity. The absolute majority perceive the state of being in love as an experience of greater force compared to when thinking of love.

To keep track of these two modes of perception, he proposes that we name and categorize them as impressions and ideas. Impressions being the more lively, forceful, and vivacious perceptions (e.g., loving, hearing, seeing, feeling). Ideas are instead the less vivid thoughts mentioned, such as the idea of love or anger.

The limits of imagination

Having established the modes of perception, he proceeds to comment on the faculty of imagination which we possess.

Nothing, at first view, may seem more unbounded than the thought of man, which not only escapes all human power and authority, but is not even restrained within the limits of nature and reality. But though our thought seems to possess this unbounded liberty, we shall find, upon a nearer examination, that it is really confined within very narrow limits, and that all this creative power of the mind amounts to no more than the faculty of compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing the materials afforded us by the senses and experience.

— Hume 2007, p. 13

At first, it seems as if he praises our imagination for having an endless capacity and reach, however, as one reads further it becomes clear that he is critically pointing out the this is but an illusion of the mind. On the contrary, our imagination is rather limited. More specifically, our imagination is limited to compounding, transposing, augmenting, or diminishing inputs. To show this, he uses two examples.

Firstly, try imagining a golden mountain. This is not something you have actually seen, yet you are able to imagine it clearly, right? Hume says that this is due to the joining of our ideas of a mountain and gold. Secondly, this can also be done with more abstract ideas such as virtue. He tells us to imagine a virtuous horse. If you have an idea of what virtue is, and have seen a horse before, you will be able to imagine this creature. However, I would add, if you do not have a clear idea of what virtue is, the process immediately breaks down and you are unable to produce the desired imagination.

Hume’s Copy Principle

This leads us to what is today known as Hume’s Copy Principle. Having presented the two modes of perception, and having showed the limitations of our mind, Hume deduces that all our ideas must be copies of our impressions. To prove this, he presents two arguments.

The first argument concerns the nature of complex ideas1. All complex and sublime ideas can be traced back to simple ideas originating from previous feelings or sentiments.

Even those ideas, which, at first view, seem the most wide of this origin, are found, upon a nearer scrutiny, to be derived from it. The idea of God, as meaning an infinitely intelligent, wise, and good Being, arises from reflecting on the operations of our own mind, and augmenting, without limit, those qualities of goodness and wisdom. We may prosecute this enquiry to what length we please; where we shall always find, that every idea which we examine is copied from a similar impression.

— Hume 2007, p. 13-14

When trying to prove this, he points to the different components of the idea of God, that is to say an “… infinitely intelligent, wise and good Being …”2 and then proceeds explaining how this complex idea is a product of our minds ability to augment the mentioned qualities. Finally, he stresses that all these different qualities, the building blocks that make up the idea of God, can then themselves be traced back to the original impressions from which they arose.

The second argument concerns a strange occurrence I briefly touched upon earlier when considering the limits of imagination and the example of the virtuous horse. In short, if a person lacks a particular sensory experience, they cannot form the corresponding ideas.

Our ability to form ideas, for Hume, is directly linked to our sensory experiences. If a person lacks a particular sense due to a defect, such as blindness or deafness, they are unable to form ideas related to that sense, like colours or sounds. However, if the sense is restored, the person can then conceive these ideas.

A blind man can form no notion of colours; a deaf man of sounds. Restore either of them that sense, in which he is deficient; by opening this new inlet for his sensations, you also open an inlet for the ideas; and he finds no difficulty in conceiving these objects.

— Hume 2007, p. 14

Similarly, if a person has never encountered a specific sensory experience, they cannot form ideas about it. For example, someone who has never tasted wine cannot understand its flavour. The argument extends to emotions and sentiments, suggesting that individuals who have never experienced certain feelings, like deep friendship or intense revenge, cannot fully comprehend them.

Interestingly, he concludes by acknowledging that there may be senses beyond human experience, which we cannot conceive because we have never felt them.

A contradiction to the principle: The missing shade of blue

Before ending the section of the origin of ideas, he presents a potential contradiction to the Copy Principle outlined in the earlier paragraphs.

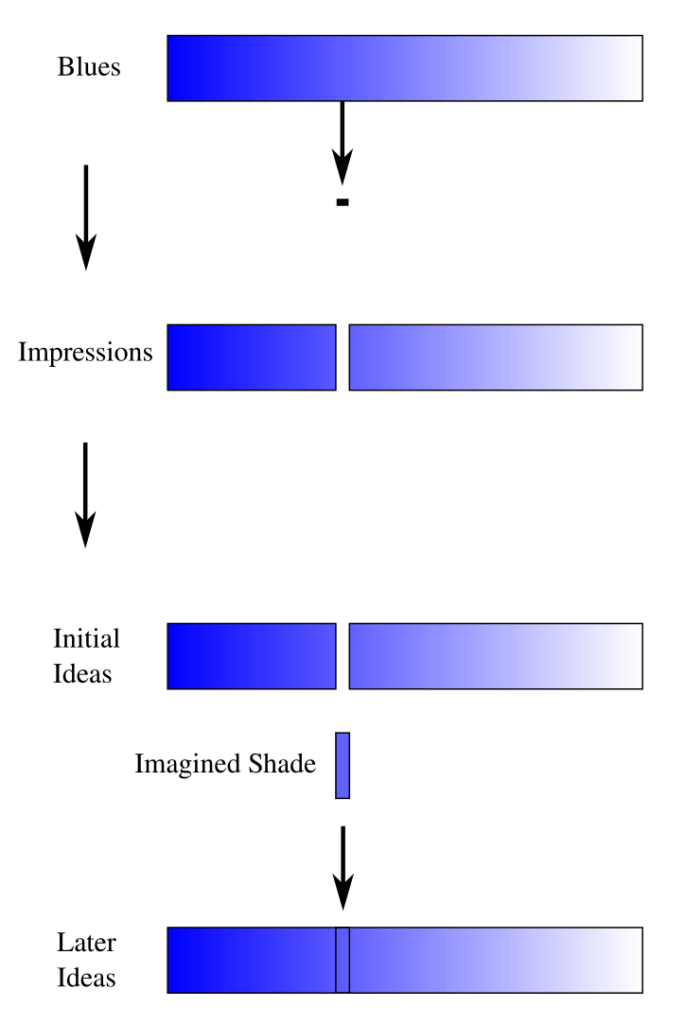

To illustrate this problem, he asks us to think of a person with 30 years of visual experience, who is familiar with all colours except for one specific shade of blue. This person is then presented with a gradient of blue shades in which that very specific shade is missing.

The question Hume finally poses after having set up this scenario is the following: Can this person imagine the missing shade without having been exposed to that particular impression (i.e. without having seen that shade of blue)? If he is able to see this shade, it would mean that ideas are not always copies of our impressions.

This contradiction has been readily discussed by scholars, and many believe that this was exactly what Hume was trying to achieve by presenting the case, to bring about discussion on the functioning of the mind. I am personally of the idea that this is best explained by the way our perception is inherently structured. We are born with the ability to see a certain spectrum of colours, whether we have had an impression of this beforehand or not.

Whatever the correct answer might be, he concludes that in the grand scheme of things, this rare contradiction is not of enough significance to alter or disprove his Copy Principle.

And this may serve as a proof, that the simple ideas are not always, in every instance, derived from the correspondent impressions; though this instance is so singular, that it is scarcely worth our observing, and does not merit, that for it alone we should alter our general maxim (Hume 2007, p. 15).

Finally, the section ends with Hume explaining how one might clarify the abstruse and complex philosophy by always tracing back the ideas to impressions. If an idea can not be traced back, it means that it is hollow, a superstition of some sort, and should hence be dismissed at once.

On the connection between ideas [Section III]

Since section III is rather short — less than two pages — and because it deals with an adjacent subject to that of section II, I have decided to include it here. In this short text Hume presents his Principles of Association, which are meant to explain how the mind organizes and connects ideas. He identifies three principles of association: resemblance, contiguity in time and place, and causation.

Though it be too obvious to escape observation, that different ideas are connected together; I do not find, that any philosopher has attempted to enumerate or class all the principles of association; a subject, however, that seems worthy of curiosity. To me, there appear to be only three principles of connexion among ideas, namely, Resemblance, Contiguity in time or place, and Cause or Effect (Hume 2007, p. 16).

- Resemblance: Ideas are connected if the objects they represent resemble each other. For example, a picture leads our thoughts to the original.

- Contiguity in Time and Place: Ideas are connected if the objects they represent are near to each other in space or time. For instance, the mention of one apartment in a building introduces an inquiry or discourse concerning the others.

- Cause or Effect: Ideas are connected if the objects they represent are causally related. For example, thinking of a wound leads to reflecting on the pain that follows it.

Hume acknowledges that proving the completeness of this theory may be difficult. He suggests examining several instances and carefully looking for a pattern that binds different thoughts together to render a principle as general as possible. The more instances examined and the more care employed, the more assurance can be acquired that the theory is complete.

Lastly, he also mentions that contrast or contrariety is a connection among ideas, but it may be considered as a mixture of causation and resemblance. Where two objects are contrary, the one destroys the other, implying a causal relationship and resemblance in their annihilation.

Final thoughts

These sections laid the groundwork for Hume’s Theory of Ideas and did so in a clear and concise manner. I have not shared much of my own thoughts throughout the text simply because I have nothing to comment on. Hume is precise and conscious of the potential problems when presenting his theories, so most of my thoughts have been brought up by him.

I will say that his use of “force” and “vivacity” to distinguish impressions from ideas seems somewhat vague. I think it can happen that an idea such as reflecting on the death of a parent is more forceful than the impression recieved from staring at a wall. He says that this happens in the case of illness and madmen, but I am fairly sure that I do not fit in either descriptions.

Hume, D. (2007) An enquiry concerning human understanding. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press (Oxford world’s classics).

- To clarify and avoid misunderstandings: In Hume’s philosophy, simple ideas are direct copies of original impressions (experiences/sensations), while complex ideas are formed by combining these simple ideas through imagination.

- See blockquote above for reference.

- This image has been borrowed and altered (cropped) from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ShadeOfBlue.svg