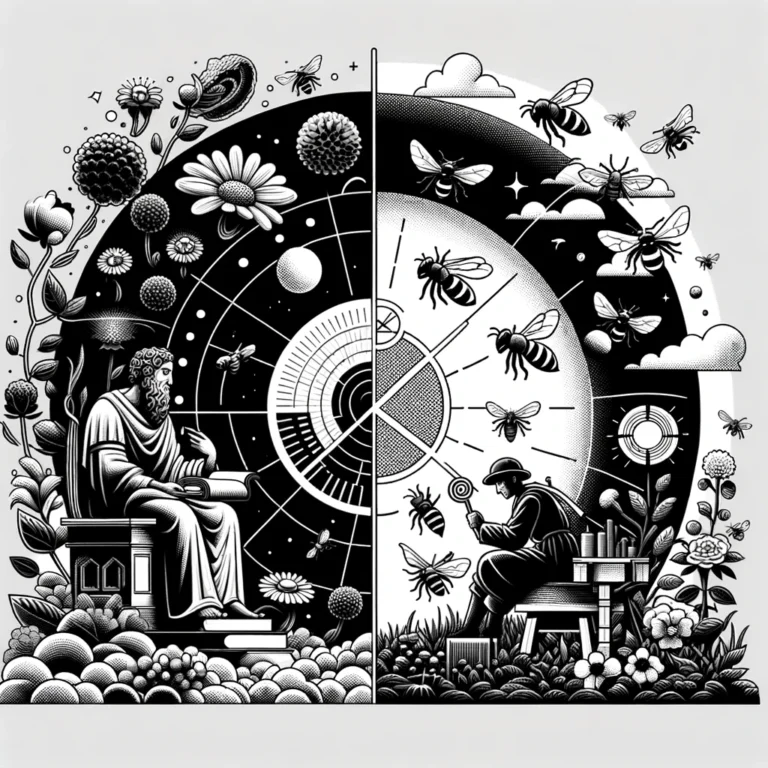

David Hume on the issues of inductive reasoning and causality

In section IV of An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding, David Hume tackles the issues of inductive reasoning and causality. He scrutinizes the basis of our knowledge about the world, questioning whether our inferences about cause and effect are truly grounded in reason. Through this examination, Hume argues that our conclusions are not the result of logical necessity but rather stem from patterns of experience.